INTRODUCTION

Notes for the user

BIOGRAPHY

CATALOGUE RAISONNÉ

Oil on Canvas

- by year

- by category

Work on Paper

- by category

EXHIBITIONS

Solo exhibitions

Group exhibitions

REFERENCES

Life & Work

Commission works

Catalogues & Journals

Newspaper articles

ABOUT

IMPRINT

SEARCH

PICTURE INQUIRY

Life & Work

Exhibitions and other activities 1971-79

Discovery of the female nude subjects

Student courses in Kornberger's studio

Facets of the nude representation

Childhood and Youth

The artistic talent of Alfred Kornberger was already evident in his exceptional performance at the school. Kornberger himself recollected how his artistic interest was first awakened by a classmate when he was twelve years old. However, without a high school finishing diploma and given the limited financial resources, it was impossible to think of entering the Art Academy. It was obvious therefore that Kornberger had to first take on an apprenticeship. He learned the trade of a lithographer.

Starting with the age of sixteen, Alfred Kornberger attended courses at the Künstlerische Volkshochschule (Artistic Adult Education School) of the City of Vienna under the directorship of Gerda Matejka-Felden. His talent was noticed and in 1951 the works of the then seventeen-year-old were shown in a group exhibition of the students of Volkshochschule (Artistic Adult Education School) at Messepalast. In addition to works by Kornberger, landscape works by Otto Muehl were also displayed, who rose to great prominence ten years later after founding the Viennese Actionism. In a journal article an unknown critic supported these »worker artists« who despite their great talent could not attend the Academy because of their professional activities.

In 1952 Kornberger was admitted to the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna in the master class of Robin Christian Andersen. Andersen had been a professor in the Vienna Academy since 1945. He was among the early combatants of the heroic years of Expressionism before World War II. He belonged to the circle of »Neukunstgruppe (New Art Group)« form around Egon Schiele, and was a member of the »Kunstschau (art exhibit)« which had developed out of the Klimt group and in the 1930s was considered as one of the leading members of the Secessionist movement who were represented regularly at the exhibitions of the Vienna Secession. As early as the 1920s Andersen directed a private art school in which he fostered a very rigid teaching based strictly on didactic principles.1 Even after his appointment as professor at the Vienna Academy, he worshiped a very dogmatic teaching principle, that was based on objective representation and a rigidly geometric form analysis. Under the title of »Anderson School«, the master class soon became synonymous with a somewhat dry, but solid, rationally-oriented teaching method. Early Andersen students who graduated from the Academy in the late 1940s included, among others, Giselbert Hoke and Friedensreich Hundertwasser. But Hundertwasser abandoned the Academy soon after a few weeks.

First exhibitions followed in 1955 with a solo exhibition at the Österreichische Staatsdruckerei (Austrian State Printing Office) in Vienna, and in 1956 in a group exhibition at the same location.

In 1957 Kornberger applied for a scholarship awarded by UNESCO for a one year stay in Bangkok, the capital of what was then Siam, now Thailand. The tender was open to artists throughout Europe, quite unexpectedly the scholarship was awarded to Kornberger. The unexpectedly high travel expenses which were not included in the scholarship were shared by the president of the Culture Association, Manfred Mautner-Markhof and support by City Councilman Viktor Matejka.

Most of the time he lived in Bangkok, and was soon noticed by influential circles of the society who purchased paintings. Kornberger also accepted portrait commissions. After his return, Kornberger described his experiences in slide shows and travel reports. In May 1958, the Museum of Ethnology in Vienna devoted an exhibition of Kornberger's works from Siam and completed the show with in-house, arts and crafts displays from this region.2 The exhibition was accompanied by a catalogue which was rather extensive for those times and which listed all the exhibited works; twelve oil paintings and forty-four works on paper in a variety of techniques. The exhibition poster was designed by Kornberger himself.

Numerous other posters that were printed during the Kornberger-exhibitions were designed by the artist himself and here his talent as a graphic artist and lithographer came in handy. For the catalogue Kornberger's former Academy Professor Robin Christian Andersen contributed the article, »Alfred Kornberger on a long journey.«3

Soon after his return from Thailand, Kornberger moved into his own studio in Vienna, on Währinger Straße 91, in the district of Währing. The unusually large studio room was thirteen meters long and five meters wide. Over the entire length of the large room there stretched a wall of windows, through which bright daylight flooded into the room. Kornberger spent as much time as possible in his studio and tried to keep the socializing with colleagues, gallery owners and museum curators outside of his studio to a minimum. It is not surprising therefore, that Kornberger did not but occasionally participate in group exhibitions. Opportunities for solo exhibitions were quite rare in any case.

In 1959 he found an opportunity for a solo exhibition, not in Vienna but rather in Stockholm. From November to December 1959, the Sturegalleriet in Stockholm exhibited a total of eighteen works, including thirteen paintings and five works of tempera on paper. 4

The next solo exhibition was some time in coming, and again did not take place in Vienna. The Graphic Cabinet of the Yugoslav Academy held in September 1963, the exhibition »Alfred Kornberger. Paintings and Drawings«, in which twenty-four oil paintings and three works on tempera paper could be viewed. 5

Rupert Feuchtmüller, director of the Lower Austrian Landesmuseum and one of the main promoters of Alfred Kornberger, wrote the text for the catalogue. Feuchtmüller elaborated on individual sample works which were symptomatic of the last ten years of the young artist. According to Feuchmüller these include the painting »Vier Frauen (Four women)« (See figure right), »Bahnhof Amsterdam (Train Station Amsterdam)«, »Portrait einer jungen Frau (Portrait of a young lady)«, »Drei irre Gestalten (Three crazy figures)« (1961), »Drei Musikanten (Three musicians)«, »Spanischer Tanz (Spanish dance)« (1962), »Passanten (Passers-by)«, »Espresso«, »Die rote Burg (The red castle)«, »Portrait mit der Pelzhaube (Portrait with the fur hat cap)« and »Die Musen (The muses)«. Feuchtmüller ended his article with the noting that though all of the young artist's quest, his creative potential lies in diversity. »If we look at these ten years of creativity unfolded in this exhibition, then one can recognizes in the works a permanent internal movement and suspense. It is never the insecurity of a searching artist, but rather only the diversity of living forces, which he aspires to form and eventually to unite.«

Rupert Feuchtmüller, director of the Lower Austrian Landesmuseum and one of the main promoters of Alfred Kornberger, wrote the text for the catalogue. Feuchtmüller elaborated on individual sample works which were symptomatic of the last ten years of the young artist. According to Feuchmüller these include the painting »Vier Frauen (Four women)« (See figure right), »Bahnhof Amsterdam (Train Station Amsterdam)«, »Portrait einer jungen Frau (Portrait of a young lady)«, »Drei irre Gestalten (Three crazy figures)« (1961), »Drei Musikanten (Three musicians)«, »Spanischer Tanz (Spanish dance)« (1962), »Passanten (Passers-by)«, »Espresso«, »Die rote Burg (The red castle)«, »Portrait mit der Pelzhaube (Portrait with the fur hat cap)« and »Die Musen (The muses)«. Feuchtmüller ended his article with the noting that though all of the young artist's quest, his creative potential lies in diversity. »If we look at these ten years of creativity unfolded in this exhibition, then one can recognizes in the works a permanent internal movement and suspense. It is never the insecurity of a searching artist, but rather only the diversity of living forces, which he aspires to form and eventually to unite.«

In its January/February issue of 1964, the art journal Alte und Neue Kunst published an article by the art historian Ernst Köller entitled »Solides Können zwischen den Extremen - Der Maler Alfred Kornberger (Solid prowess between the extremes - the painter Alfred Kornberger)«. After a detailed biographical introduction Köller expounds on individual sample of the works, six of which are reproduced in the article and undergo thorough stylistic analysis. For the earliest picture, »Vier Frauen (Four women)« from 1954, Ernst Köller noted that here is »a strong urge for adherence to the ›monumental‹ is noticeable. One is reminded of the psychologically ›defused‹ pictures of the early Schiele, implying that Kornberger is quite within the tradition of the Viennese painting of the period before the First World War which he in turn develops further.«6 Köller further discusses the picture »Totenzeremonie (Death ceremony)« from 1958, where he described the color as a new design element for Kornberger.

In Kornberger's works from 1959, such as the »Portrait einer jungen Frau (Portrait of a young lady)«, Köller sees the artist »standing at the crossroads between expressive abstraction and committed/bound confrontation with the with the phenomenal world«. Kornberger had chosen the second option.7 In the 1961 painting »Drei irre Gestalten (Three insane figures)« (based on Dances by Harald Kreutzberg) from 1961, Kornberger appears to be deeply influenced by Kreutzberg's dance art. Their »non-gaze, their stumbling, their imprisonment in a completely dead environment - all this is of high, immediately comprehensible symbolic power.«

Köller includes Kornberger among those artists who orient themselves towards great role models and develop these further. »It would be wrong to count him in the company of innovators and revolutionaries, he is one of those temperaments that are willing to hear the message of the great old masters, to understand and make them virulent for themselves.« In the »Bildnis der Gattin (Portrait of the wife)« and the »Die Namenlosen (The nameless)« from 1961, Köller recognizes the influence of the Cubist works of Picasso and Braque from the period around 1908. Especially with the »Namenlosen (Nameless)« there is an »expression of Petrifaction, Numbing, Loneliness.« »As with all typical Austrian artists, Kornberger also held on to the primacy of the expressive content, form and style are never autonomous.« According to Köller, the painting »Das Quartett (The quartet)« from April 1962 shows in turn the late Cubism of Picasso. »But what is in Picasso a riot, assault, painful strain to the utmost, transforms into the idyllic with Kornberger. The opposition becomes juxtaposition; the representations do not confront each other but are together. In its own way the image is an apotheosis of the unifying power of the arts.«

The painting »Die Verurteilten (The condemned)« from 1963 reflects a »tempered pessimism« which represents one of the fundamentals of Kornberger's creations which, similar to the painting »Der Trinker (The drinker)« form the same period, are witness to »the persistence of the teachings of cubist painting, their treasure of forms are in turn depicted here in the sense of simplification and creation of an overview of the pictorial scene.« The picture »Frau im Lehnstuhl (Woman in an armchair)«, from 1963 reminds the author of Picasso's »classical« period. The person counters, »alone, melancholic« acts in turn on »the imprisonment of the chair, the emptiness of space are powerful experience and sensation factors.«

Paradigmatic for Kornberger's tendency is the »Frau am Strand (Woman on the beach)« (see figure left) from 1963 that leads his work into »gentle sadness and resigned melancholy.« According to Köller the »Frau am Strand (Woman on the beach)« is a painting »in which everything swings, starting from the soul of the painter, over to the gentle curviness of the bay and the mountains, to the rhythm of the crouched body of the woman, which in turn is meant to monumental and fateful. The boat in the middle ground is consciously conceived of as the female body. It separates the two figures, abstracts from these the figure in the background, which motionless and the faceless confronts an imaginary distance. The boat, however, turns into a messenger of an alien world, which seems to be irrevocably stranded here, on the coast of the lonely.«

Paradigmatic for Kornberger's tendency is the »Frau am Strand (Woman on the beach)« (see figure left) from 1963 that leads his work into »gentle sadness and resigned melancholy.« According to Köller the »Frau am Strand (Woman on the beach)« is a painting »in which everything swings, starting from the soul of the painter, over to the gentle curviness of the bay and the mountains, to the rhythm of the crouched body of the woman, which in turn is meant to monumental and fateful. The boat in the middle ground is consciously conceived of as the female body. It separates the two figures, abstracts from these the figure in the background, which motionless and the faceless confronts an imaginary distance. The boat, however, turns into a messenger of an alien world, which seems to be irrevocably stranded here, on the coast of the lonely.«

In June 1964, the Österreichische Staatsdruckerei (Austrian State Printing) organized another Kornberger exhibition in their showrooms in Wollzeile under the title »Alfred Kornberger. Ölgemälde (Oil Paintings) 1958-63«.

A year later in 1965, Galerie Kontakt in Linz organized the exhibition »Alfred Kornberger. Ölgemälde (Alfred Kornberger. Oil Paintings)«. Just as a year earlier Peter Baum of Oberösterreichische Nachrichten (Upper Austrian News) had criticized Kornberger's tendency towards mainly great role models, so now his colleague Herbert Lange argued that it was exactly this constant orientation towards the great mentors which constitutes one of the great weaknesses of Kornberger's art. »If he unconsciously as a kind of pictorial ›animal voice imitator‹ - together with Cézanne, Picasso, Braque, Matisse, and a little sophisticated naivety - manipulates surrealism, he should have no need of it anymore from the day when his intellectual maturity definitely match his the technical skills.« For Herbert Lange, this is thus apparently a kind of transitional stage in the development process of the artist not having yet reached his maturity. »For the time being he is a kind mulus: for a child prodigy to experience and as master to make dependent« 8

Painting was indeed to a great degree Alfred Korberger's great passion. But he was also interested in new forms of expression that were current in the art scene of the 1960s. Kornberger approached these new currents less from a theoretical-discursive point of view, but rather from that of a purely practical and creative application. To this end his great handicraftsman's talent came in handy. In addition to his training as a graphic artist and lithographer he had, for example, repeatedly designed fashion dresses for his wife, made dolls out of cloth which incidentally sold like hot cakes, and created the whole furnishing for his large studio almost all by himself and produced ceramic sculptures and painted ceramics.

The works of Fluxus movement with their material images inspired Kornberger to create comparable works. In his »Komposition mit Puppen (Composition with dolls)« from the year 1966, he placed a large number of small dolls in a kind of showcase with many small compartments. As a macabre detail he left the dolls dangling from the gallows. In the same year he also designed several »Quadri mobile«. The basis for the latter work was the system of the building blocks for children which Kornberger adapted to his purpose. The cubes were painted with a different color on each page, and could be moved and rotated by the viewer. In the manner of a »do-it-yourself plastic« the viewers could freely build their own color cubes according to their own color compositions, in a way mimicking the colors of a season.

At the same time Kornberger painted oil paintings in which he worked out the theme of machines. The paintings show motives with simple machine structures, cogs, hubs, cranks, gears and similar components or mechanical operations. In 1968 there followed a plastic version of this machine constructions. Wheels, rods and hinges made of wood moved together and could be set in motion by a small engine. The artwork thus appeared as kinetic object.

In June 1967 Alfred Kornberger took part in an exhibition at the Kunsthaus Krems. On this occasion he showed for the first time his »machine-like construction, which he considered inferior to human feelings«.9 Out of the series from machine motives the picture »Signale vor gelbem Hintergrund (Signals in front of a yellow background)« and »Automatische Bewegung (Automatic movement)« were highlighted in the press.

According to an article in the Zeitschrift für Unfallverhütung (Journal of Accident Prevention) in 1967, Kornberger had, in his own words, come into encountered the thematic of the machines and technique through his work on graphical commissions from the Accident Prevention Services. »Kornberger was fascinated by the, otherwise little known to artists, of the inner world of machines and apparatus of wheels, levers, pistons and joints, pipes and cables, transport, the chemical laboratory and scientific mysticism of electronics. As a result of this process, he created oil paintings of machines in which the constructed objects are no longer in the usual photographic, calendar book-like manner.«10

In an extensive solo exhibition, which the Kulturhaus Graz dedicated in August 1969 to the works of Alfred Kornberger, the machine images were also the focal point of the exhibition (see figure right). However, they were not greatly appreciated by the critics. Dietmar Polaczek from the Graz's Neue Zeit puts the most recent group of works at the center of his article: »He is taken with the machines, and indeed with their decorative vitality. Expressionism is once again eliminated, only the gay and progressively pounding pistons and joints meet the twitching fill the stretched surfaces. The movements are hereinafter more hectic, the script hardly appearing earlier, is liquefied, Kornberger moves in a somewhat surprising manner to the vicinity of Action painting.«11

In an extensive solo exhibition, which the Kulturhaus Graz dedicated in August 1969 to the works of Alfred Kornberger, the machine images were also the focal point of the exhibition (see figure right). However, they were not greatly appreciated by the critics. Dietmar Polaczek from the Graz's Neue Zeit puts the most recent group of works at the center of his article: »He is taken with the machines, and indeed with their decorative vitality. Expressionism is once again eliminated, only the gay and progressively pounding pistons and joints meet the twitching fill the stretched surfaces. The movements are hereinafter more hectic, the script hardly appearing earlier, is liquefied, Kornberger moves in a somewhat surprising manner to the vicinity of Action painting.«11

Endpoint of this machine images is the object painting »Komposition mit prästabilisierter Harmonie (Composition with pre-established harmony).« This enables the representation of mechanical sequences using wheels, hinges, balls and the like.

»The final consequence: the movement in reality. Without knowing the Kinetic Cramer and Co., Kornberger is also suddenly to jerks of the spinning wheels, tennis balls running in grooves and the like, the fascinating playful banter fascinating. Internal consistency is not quite displayed in the exhibited object of this type: movement relationships that are indispensable for understanding the purely mechanical are hidden behind the mounting plate, and through the deliberately aimless also emerges an aimless machine.«

For all the critical distance Dietmar Polaczek acknowledges an individual creativity in the works of Kornberger, which stays clear of Epigonism. »Kornberger does not build on the foundations of the great predecessor further, he rather builds next to the building of modern art his own towers, which unintentionally has a lot of similar traits.« The critic from Kleine Zeitung classified them differently however. The later sees in the work of the Viennese, »an appropriation of formal and stylistic achievements of modern painting since Cézanne. His ›Siamesisches Dorf am Fluss (Siamese village at the river)‹ is painted à la Cézanne, his ›Quartett (Quartet)‹ à la Picasso, his ›Der Alte (The Old Man)‹ à la Giorgio de Chirico, his ›Portrait eines alten Mannes (Portrait of an old man)‹ à la Beckmann, his ›Madame Rose‹ à la Otto Dix, his ›Composition with pre-established harmony‹ is a showcase à la Stenvert, his motion pictures from 1967 are finally dabbed à la Arnulf Rainer.«12

The critic of the Graz's Wahrheit takes the same line. The latter notes with a touch of irony, »If the works of Van Gogh, Giorgio de Chirico, the painting publican Henri Rousseau, the Art Nouveau painters, the Pop and Op-artists one day be destroyed and the vast oeuvre of Kornberger survive, no one would need to concern themselves with the art history of these years: Kornberger has painted it all, his images span the most important directions in a large arc.«13

Exhibitions and other activities 1971-79

In 1971, Kornberger's son Christian was born. Only two months after the birth of the child the family moved into a new apartment in Vienna on Aumannplatz Währing, Währinger Straße 162, where the new apartment was comfortably within the walking distance of the studio. The former studio apartment now was used exclusively for work.

From November to December 1971 the Galerie Wittmann in Vienna's 13th district, Maxingstraße 11, presented an exhibition of the recent works of Alfred Kornberger. In the Wiener Kurier, Alfred Muschik describes these works in detail, »The starting point was an image on a nice brown and red background which depicted a dancing man in harlequin dress. From this picture Kornberger operated the motive of the movement and modified it many times, first in wave-like forms meandering, multi-colored ribbons, then the outlines of figures that display in turn segmentations in a moving-schematic manner. The development went from a mess of colors and shapes to greater clarity.«14 Alfred Kornberger himself writes about the motivation for this new phase of work (see figure right),»I try now to transfer the movement to the people themselves. Above all, it is the dancing, rhythmically moving person I try to capture formally.«15

From November to December 1971 the Galerie Wittmann in Vienna's 13th district, Maxingstraße 11, presented an exhibition of the recent works of Alfred Kornberger. In the Wiener Kurier, Alfred Muschik describes these works in detail, »The starting point was an image on a nice brown and red background which depicted a dancing man in harlequin dress. From this picture Kornberger operated the motive of the movement and modified it many times, first in wave-like forms meandering, multi-colored ribbons, then the outlines of figures that display in turn segmentations in a moving-schematic manner. The development went from a mess of colors and shapes to greater clarity.«14 Alfred Kornberger himself writes about the motivation for this new phase of work (see figure right),»I try now to transfer the movement to the people themselves. Above all, it is the dancing, rhythmically moving person I try to capture formally.«15

Harald Sterck of the Arbeiter Zeitung also describes the undulating contours of reduced figures and sees in them the danger of stereotyping, »The problematic of such a procedure, which he shares with many of his contemporaries, is obvious: Once the repertoire has been developed and tried out, there threatens Schematism.«16

In 1973 the City of Vienna presented the competition »Der Mensch und die Stadt (Man and the city)«. 118 artists participated in this contest, including Alfred Kornberger. The winner of the competition was Karl Anton Fleck.17 The results of the contest were presented in the Festwochenausstellung from May to August in the Vienna Künstlerhaus.

In June 1974, Alfred Kornberger for the first time had an exhibition at the Zentralsparkasse and Kommerzbank of the City of Vienna, and in fact at the branch office in Gersthof near his studio. In the accompanying text the Kornberger discussed the works, which in 1971 followed immediately the moving contour figures, »The pictures become somewhat static. The rhythm has shifted to the inner - the forms of the people emerge clearly once more.«18

In 1975 Kornberger premiered in the Bezirksmuseum Währing in Vienna. Like the Zentralsparkasse this institution would also play an important role for Kornberger in the coming years. The artist increasingly turned to a limited local interest group that developed in the immediate vicinity of his studio. An increasingly important voice for his art was the Bezirksjournal Währing, which reported regularly on Kornberger's exhibitions and studio activities. The artist attached great importance to good relations with local authorities, with the district council and, occasionally also the representatives of the city authorities.

Kornberger's exhibitions in the Bezirksmuseum Währing were regularly accompanied by articles about his art, written by the director of the Museum District, Helmut Paul Fielhauer. He specially cherished the idiosyncratic personality of the artist who is not ready to subject himself to the rules of the art business or the art of self-dramatization.19 By the latter Fielhauer means the process that becomes more and more evident from the early 1970s. Kornberger increasingly eludes the gallery business, spends less effort for participating in major exhibitions and often contents himself occasionally with less prominent venues for his solo exhibitions. Increasingly, galleries in the country, banks, butcheries and bakeries became his favorite gallery spaces. Kornberger compensated for his refusal of the usual exhibitions with a tremendous activity in his studio, where professional nude models were almost always present, where he held regular art courses for beginners and advanced art students and held artist gatherings and exhibitions.

At the same time, there were occasional exhibitions in galleries abroad. From March to April 1976 Stuttgart Galerie Hoss showed the exhibition »Akt heute (Nude today)« where the works exclusively dealing with female nudes were presented.20 In the Stuttgarter Zeitung, the painting »Sitzende vor schwarzer Tür (Sitting in front of black door)« was mentioned among other works.21

In a 1977 edition of the Bezirksjournal Währing, Alfred Kornberger explained to the Karl Prinz how he chose his subjects. »Especially light conditions make an unusual object suddenly very appealing. Suddenly you experience and discover it all at once.« Kornberger first draws a sketch, »that is why I always carry a ›notepad‹ in my jacket.« The subject is often painted much later, it may take even years. As Kornberger puts it, »I cannot paint ›Still Lives‹. I prefer to work on the subject of man. Lately, more and more landscapes are added.«22

Since 1974, Kornberger and his family had been going regularly to the Waldviertel in Lower Austria, where he stayed in the area of Ottenschlag and Traunstein near relatives of his grandmother. Just as in the Vienna studio Kornberger was also untiringly active during these stays (see figure left). Scarcely a day went by during which he did not work simultaneously on several works, mostly drawings on paper. The encounters with the barren landscape, the wide open fields and the endless horizon, which he visited during different seasons, inspired Kornberger to motifs that had until then hardly played a role in his work. In numerous pencil and crayon drawings Kornberger captured the topography of the landscape, their lonely farmsteads, deserted villages and sparse groups of trees. In this process Kornberger developed a graphic structure. With a few hatchings of the pencil the outlines and shadings were captured, in the color pencil sheets he brought pastel tones to life.

Since 1974, Kornberger and his family had been going regularly to the Waldviertel in Lower Austria, where he stayed in the area of Ottenschlag and Traunstein near relatives of his grandmother. Just as in the Vienna studio Kornberger was also untiringly active during these stays (see figure left). Scarcely a day went by during which he did not work simultaneously on several works, mostly drawings on paper. The encounters with the barren landscape, the wide open fields and the endless horizon, which he visited during different seasons, inspired Kornberger to motifs that had until then hardly played a role in his work. In numerous pencil and crayon drawings Kornberger captured the topography of the landscape, their lonely farmsteads, deserted villages and sparse groups of trees. In this process Kornberger developed a graphic structure. With a few hatchings of the pencil the outlines and shadings were captured, in the color pencil sheets he brought pastel tones to life.

It may lie in the essence of the artist that he prefers art galleries that are distinguished purely geographically from the purely traditional urban galleries. In the case of the latter galleries the commercial aspect was rather less of an important factor than the social bonding of he exhibited artists with a committed fan base that turned up regularly for the openings and artists' festivals. It may be significant that even Kornberger's colleague Karl Anton Fleck exhibited at about the same time in these now hardly known galleries. Hence, Fleck showed his works in 1978 also at the Galerie Arcade in Mödling and exhibited in the same year also in the Galerie am Doktorberg, where Kornberger was also represented. Fleck played simultaneously in the same year also a solo exhibition of portrait drawings at the Museum des 20.Jahrhunderts (Museum of the 20th Century) in Vienna.23

On 5 April 1978, Alfred Kornberger was invited to a screening of six short films at the district office in Vienna-Währing. The first of these films produced by Kornberger himself deals with the topic »Kunst und Wirklichkeit (Assoziationen und Reflektionen) / Art and Reality (associations and reflections)«, and describes the work of the artist and his search for suitable motifs. In the second film »Und es blühen die Rosen (And there bloom the roses)« Kornberger is concerned with the question of the meaning of life and its pursuit. The third film, »Alle Jahre wieder (All the Years Again)« deals scrutinizes the meaning of Advent in the face of an increasingly hectic consumer society. The fourth film »Franz Schmutzers Initiativen (F. S. 's Initiatives)« describes the realization of the idea of establishing an art gallery in a coffeehouse. The fifth film, »Wochenende (Weekend)« and the sixth film, »Hausmusik (House Music)« both show the petit bourgeois life through portrayal of the weekend and leisure time, with many scenes taken from the life of the artist himself. 24

Kornberger had shot and edited all these films himself. He embraced this new medium and was open to cinematic experimentation. Kornberger produced another film at the same time about his new subject »Zeus«. In his series of paintings Zeus assumes the shape of a bicycle in the role of the partner of a young woman. After a wild and violent dance with this bike it is finally destroyed in the movie by the woman, only the bicycle seat survives the destruction. The film was first shown at the Museum des 20. Jahrhunderts (Museum of the Twentieth Century).

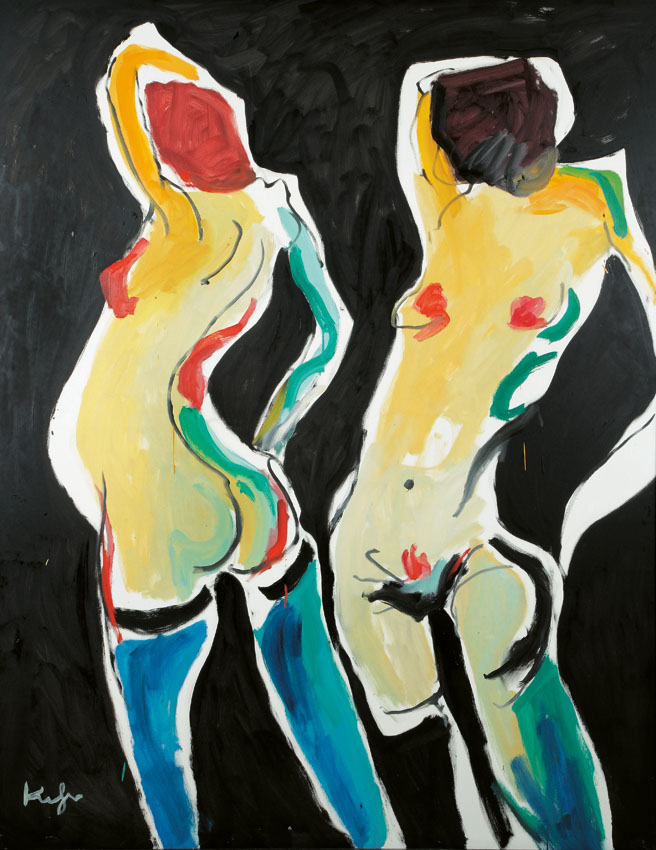

Discovery of the female nude subjects

The separation of the living and working areas, which was completed with the relocation of the family of the artist to their own apartment in 1971, allowed an intensified professional work with nude models (see figure right). From this moment on Kornberger worked more intensely with female nude models, which were to occupy the dominant position in the subsequently mature works of the artist.

The separation of the living and working areas, which was completed with the relocation of the family of the artist to their own apartment in 1971, allowed an intensified professional work with nude models (see figure right). From this moment on Kornberger worked more intensely with female nude models, which were to occupy the dominant position in the subsequently mature works of the artist.

In 1973 Kornberger noted the following remark which was reprinted a year later in the accompanying text for the exhibition at the Zentralsparkasse, »Man is at the forefront of my artistic work. Intensive drawings of nude models, [...] starts with the elucidation of the people. In addition to the drawings, the first oil paintings emerge out of this subject.«25

1975, Helmut Paul Fielhauer noted within the framework of the exhibition in the Bezirksmuseum Währing, »that Kornberger has found its way in recent years (though by no golden laurel grove). Through the constructivist machine paintings he has arrived at the man standing behind these machines. This is still the machine-man, the modern machine-man. But increasingly it is the man in his daily life and the dissolved and beloved man (who of course in dialectical contradiction has not lost anything of his often suddenly perceived lack of transparency.«26

On the occasion of the exhibition »Zurück vom Urlaub - Zeichnungen und Bilder aus dem Waldviertel (Back from vacation - drawings and paintings from the Waldviertel)«, displayed in the Bezirksmuseum Wien-Währing in October 1977, the artist Karl Benkovic wrote an article entitled »Landschaft-Gestalt (Landscape-figure)«, wherein he discusses the nude depictions of his colleague Alfred Kornberger. Benkovic makes a direct comparison between the landscapes and female nudes of the artist.

In the nude the author discovered anthropomorphic landscapes, which are however far from being regarded as mere erotic objects, »Today, it is easy ›to see‹ the landscape as a huge reclining figure without further ado, and terms such as facial or body landscape, are not entirely foreign. Kornberger's female nude drawings that the artist has created in the recent years should also be considered from this standpoint, where the almost manic obsession in working with only this picture type is striking. And it is precisely because of this that the overall view of the whole show is so important for this work, otherwise there would remain only the extremely annoying repetitions of the strained (erotic) pictorial themes. The pictures, however, do not deserve such a treatment. The entire wealth of the drawings is only apparent when one recognizes these voluptuous women figures as forms ›melted‹ in timelessness and as marks of nature.«27

Benkovic observed in his colleagues Kornberger the obsession with which he had focused on the subject of the female nude in recent years. This exclusivity would be reinforced in the subsequent years. This concentration on the nude models however went hand in hand with an increasing immobility of the artist and stronger entrenchment in his studio. Kornberger was hardly amenable for long trips. Only once in a while did he travel abroad in the later years, the last longer stay was in 1986, in Venice.

Nevenka Kornberger describes her husband as a man who did not want to be alone. He preferred to be surrounded by as many models, students and friends as possible. Kornberger preferred to have the public in his studio and held court in the studio at the same time. It was again and again the setting for cultural events such as like poetry readings and exhibitions, but also for large-scale artists' gatherings, in which art lovers, potential buyers, interior and local politicians were also present. 28

Student Courses in Kornberger's studio

Alfred Kornberger regarded his studio increasingly as a public area, to which each and every interested person had access. From about 1980 Kornberger started to offer painting and drawing classes for beginners and advanced students that were available for a small course fee. Kornberger reserved almost daily the time from 7pm to 9pm, and the whole of Sunday mornings, for these courses. The courses were made known primarily through advertisements in local media, such as the Bezirksjournal Währing or through the announcement of each new course program during the opening of exhibitions.29

For the beginners of his courses Kornberger set almost no requirements. The joy for creativity was the decisive factor which had to be encouraged. In his course programs Kornberger called for the bringing to life of the artistic forces without being intimidated by rules and norms, »Drawing and painting in the studio: I am convinced that many people feel the need to be creatively active- to live out life artistically - to experience themselves - to communicate. That is why, I appeal to all those who would like to draw and eventually paint, or have already been drawing or painting, have tried to communicate artistically, have tried to transform their impressions, be it line or color, who lost the courage and put aside the pencil and the, who had never taken up the tools before because they told themselves, ›I could never do it‹, I turn to all these art friends to help them to truly realize their artistic will. I want to teach them to see and to transform what is ›seen‹ into lines, surfaces and colors.«30

»The artistic program extends from the exact drawing up to free improvisation and work with colors, to finding and creating one's own personal expression. The courses are built on this principle and therefore appropriate for any willing person. I hope that one of these he course would also be of interest to you, and I would be glad to welcome you into my studio. Prof. Mag. Art. Alfred Kornberger.«31

The courses for beginners and the advanced students were apparently no great burden on the artist. They appeared rather to be an opportunity for him to work in a circle of informally formed group. The work in front of the models stood mostly at the center of his classes. Hence, the drawing techniques dominated the courses. Together with his students Kornberger produced drawings of the models one after another. During the sessions with model Kornberger sometimes worked obsessively under great time pressure to capture the subject in all its facets in rapid succession.

Facets of the nude representation

At times Kornberger transcended the traditional mediums during nude paintings. Kornberger, for example, created a mixture of sculpture and painting with a series of portable nudes, which he displayed in the exhibition »Landschaften (Landscapes)« in 1977 in the Galerie am Bauernhof in Anzing, Lower Austria. This farmhouse was turned into an exhibition center by the artistically active couple Gertraud Schmid-Taschek and Franz Xaver Schmid in 1975. Here, numerous exhibitions took place in the following ten years, that were a relatively homogeneous and constant display of the works of some fourteen artists, including Isolde Jarina, Karl Benkovič or Lieselott Beschorner. Here Kornberger found a convivial circle in a friendly atmosphere. His series of portable nudes consisted of cardboards out of which the outlines of the figures were cut. These cardboard patterns were versatile and could be presented on any wall, or even in the open air. In addition to being added plastic effects Kornberger made the breasts of the models on the cartons out of plastic, he produced their forms by imprints on the models. Photos documented the process of the molding of the breasts off the models, the different placings and transporting of the patterns, always accompanied by the witty band of fellow artists and friends. The whole displayed the features of ›Happening‹.

In 1978 Kornberger took part in the exhibition with the motto »Garten der Lüste. Hommage à Hieronymus Bosch (Garden of Earthly Delights. Homage to Hieronymus Bosch)«, also held in Anzing, Lower Austria. Kornberger showed a picture with two plump ladies in garter clothing who are playing with a bike. He writes in the exhibition catalog, With my contribution to the subject ›Homage to Bosch‹ I try to capture the present situation of man, and show a small segment of the ›Garden of Earthly Delights‹, in which we live today.«32

In 1978 Kornberger took part in the exhibition with the motto »Garten der Lüste. Hommage à Hieronymus Bosch (Garden of Earthly Delights. Homage to Hieronymus Bosch)«, also held in Anzing, Lower Austria. Kornberger showed a picture with two plump ladies in garter clothing who are playing with a bike. He writes in the exhibition catalog, With my contribution to the subject ›Homage to Bosch‹ I try to capture the present situation of man, and show a small segment of the ›Garden of Earthly Delights‹, in which we live today.«32

From the theme of the female nude joined with a bike there emerged the so-called »Zeus« cycle, on which the painter had been working continuously since 1977. Alone until 1984 Kornberger created hundred works on this subject using various techniques such as, oil paintings, gouaches, pastels, pencil and crayon drawings, as Dieter Schrage wrote in the article, »Alfred Kornberger. Zeus bedrängt eine Frau (Alfred Kornberger. Zeus harassed a woman)« for the journal Vernissage.33

Schrage reported in detail how Kornberger arrived at theme, »At the time he made drawings of a model with a bicycle and called this series ›Zeus‹. The supreme ruler of the gods with his penchant for love adventures masculinized himself in the shape of a bicycle, always abstracted rode, a machine: Zeus, the masculine, the transumter, a constructor and the constructed at the same time. Even in the works of the artist, Zeus transmutes himself.

The figure of the bike takes a backseat; the couple is pushed more and more to the forefront, marked by a strange semi-cranial form. Kornberger 1983-84 created a new series on the topic (see figure right above). In these images, »this often very freely and impulsively painted rode structure dominates again, sometimes doubling or tripling itself, often in a delightful contrast to the female form.«34

The »Zeus« cycle in 1985 formed the subject of two exhibitions at the same time, both of which were held in May and June. In the branch office of the Zentralsparkasse Meidling the City of Vienna was presenting the exhibition »Bilderzyklus: Zeus bist du es? (Picture cycle: Zeus is it you?)« and the United Art Gallery, Vienna, showed »Alfred Kornberger: Akte - Zeus - Akte. Arbeiten auf Papier (Alfred Kornberger Nudes - Zeus - Nudes. Works on paper)«. In the journal Vernissage the cycle was described as follows, »Kornberger has created an extensive cycle of paintings around this eternal subject, where in a contemporary variation Zeus is constantly transformed into a machine, in order that power to reveal the power that shapes our present and dominates our lives.«35 Similarly, in 1985 Dieter Schrage published an article in the journal Visa Magazin. Z-Magazin für Visa Kunden.36 This contribution largely corresponded with the article that the same author had published a year ago about the topic of the »Zeus« cycle in the journal Vernissage. Schrage stressed that an exhibition of the works of Kornberger in the Viennese Künstlerhaus is long overdue.

Alfred Kornberger had been a member of the Vereinigung Bildender Künstler (Association of Visual Artists) of Vienna since 1979. This membership of the Künstlerhaus Vienna provided him with additional exhibition opportunities, which he used occasionally, but by no means regularly. In 1980 and 1983 he participated in Kinogalerie at Künstlerhaus with a solo exhibition of his latest works. In 1984 Kornberger was represented with three paintings in the exhibition »Bildende Kunst aus Österreich. Malerei - Graphik - Plastik. 36 Künstler aus Österreich (Visual art from Austria. Paintings - Graphics - Plastic. 36 artists from Austria)« which offered an overview of the current work of the members of the Künstlerhaus. The exhibition was first shown in Munich, before it was seen in the exhibition center in the Berlin TV tower. Kornberger was represented with a total of three works.37

In 1984 Kornberger appeared as a writer for a change. He wrote a short text on the artistic contribution of his fellow painter Karl Benkovič at the »Präsentation am Bauernhof (presentation at the farm)« in Anzing.38

In this essay Kornberger critically examines the notion of the rituals. In his opinion rituals are emptied of their necessary spiritual content in our times. The modern times delight only in material things and raise them into a fetish. Even art takes on a kind of ritual function, Kornberger continues in same article continues, »The art, since ever the mirror of the times, shows exactly the situation in which man finds himself today, and with it this realization has also already become a ritual. However, a ritual which neither runs in a specific direction and neither is subject to a certain time-rhythm. That would also explain perhaps why the art is autonomous, and therefore can be manifested independent of all temporal afflictions.«

In 1985 Alfred Kornberger was awarded title of professional title of Professor. While Kornberger was rather scarcely present in the established art scene, he was always enthusiastic about unusual and surprising ideas for exhibitions. Through his close contacts with the local Party leaders of the district Währing, he came up with the idea to show pictures in the Währinger Park on the occasion of the swearing of soldiers of the Armed Forces on 26, October 1986. The show took place in a tent of the Armed Forces. The theme of this for only two days schedule exhibition was cycle »Gedanken gegen die Macht (Thoughts against power)«, that is pictures that were against the war. At the beginning of 1987 Kornberger showed this series again under the title »Alfred Kornberger. Bilder für den Frieden, gegen den Krieg (Alfred Kornberger. Paintings for peace, against the war)« in the Viennese Galerie im Tunnel.

Overall, the second half of the 1980s was marked by unusually intensive exhibition activities of Kornberger that took place in galleries and institutions with different formats and was sometimes accompanied by prominent figures from politics and culture. In the summer of 1986 Kornberger took part in the Wandspielwochen of the City of Vienna. Twenty-seven artists were invited to present large-scale works in public spaces. Kornberger's contribution was a billboard with a largely non-representational depiction, which made use of graphical shortcuts from the graffiti art.

In October of the same year Kornberger showed his latest works under the title of »Alfred Kornberger. Sinnbildliches. Malerei, Grafik, Plastiken (Alfred Kornberger. The Allegorical, Painting, Graphic, Plastics)« at the Viennese Gallery Flutlicht. Worthy of notice was above all the sculptural works of the artist, which would occupy an increasingly important role. On 13 November 1986, in Raiffeisenbank, Branch Währing, the exhibition »Alfred Kornberger. Große Welt im Kleinformat (Alfred Kornberger. Big world in miniature)« was inaugurated by the current President and former Federal Minister for Science and Art, Heinz Fischer. The personal presence of the Minister undoubtedly meant a high honor for the artist.

At the beginning of 1987 Kornberger showed the graphic cycle »Venedig (Venice)« in the United Art Gallery in Vienna which was developed during a stay in Venice. The Vienna city motifs and themes from the Waldviertel area equally stood at the focal point of artist's interest in exclusively topographical scenes, depictions of people were not intentional.39 This cycle documents the constant eagerness to work, which Kornberger displayed during his travel stays. However, Kornberger hardly travelled abroad later, he preferred to stay in his studio or in his familiar rural stations in the Waldviertel and the Burgenland.

Apart from these topographical views, the theme of the female nude was also to remain the focus of Kornberger's exhibition activities in the future. Twice in 1998 Kornberger presented works in the Galerie Maringer, in St. Pölten, under the title »Alfred Kornberger: Erotische Kunst. Ölbilder, Aquarelle (Alfred Kornberger: Erotic Art. Oil paintings, watercolors).«

One of the highlights exhibitions up to that time by Alfred Kornberger was a solo exhibition at the Hausgalerie in Künstlerhaus Vienna, where from April 5 to May 7, 1989 under the title »Alfred Kornberger. Bilder (Alfred Kornberger. Images)« his work could be seen. Dieter Schrage, curator of Contemporary Art at the Museum of Modern Art in Vienna, and longtime friend of the painter, gave the opening speech. For the duration of the exhibition, Kornberger posted a huge transparent on the facade of the Künstlerhaus with oversized depiction of his painting »Vier Striptease-Tänzerinnen (Four striptease dancers)« from 1984.

In the course of this exhibition Kornberger became once again aware of the lack of a comprehensive publication about his work. Therefore, he decided to produce the book, »Alfred Kornberger. Bilder und Graphiken aus den Jahren 1974-1990 (Alfred Kornberger. Images and graphics from the years 1974-1990)« which appeared in 1991 published by the artist himself. This book was the first monograph of the artist's work. On 238 pages 220 works were illustrated that the artist had selected mostly out of works from the late 1980s. Contributing authors for the book were Dieter Schrage and Karl Benkovič. As a trained graphic artist Kornberger put greatest value in this publication on the optimal reproduction of his paintings.

Under the title »Frauen, Zeus, Affen, Reißnägel und Anderes. Anmerkungen zur Malerei von Alfred Kornberger (Women, Zeus, monkeys, thumbtacks and others. Remarks on the paintings of Alfred Kornberger)« Schrage takes a look back at the manifold works of Kornberger. He emphasizes the ever-recurring theme of women's representation, be it cabaret pictures with strippers, dancers from the »Moulin Rouge« or »women out of a Fellini film«. Schrage aptly remarks, »happily and very masterfully he also cultivated the seemingly obscene.«40 Within this group of »voluptuous-expressive women-figures«, the »Zeus« cycle stands out which the artist had created repeatedly over the years. According to Schrage the multiplicity of Kornberger's subjects span »from the fully nude to across the dominated portraits up to abstract still life«, from among which »the author highlights in particular the noble thumbtacks - still life«.

Dieter Schrage finally turns to the current, in 1989 created cycle »Affe und Frau (Monkey and woman).« In ink-wash drawings watercolor sketches the artist depicts »the tragic-grotesque play between the sexes. A times it is an approachement, at times it is a dance, sometimes it is enticement and rejection, and sometimes it is masturbation, often dressage.«

In Kornberger's own words the cycle »monkey and woman« refers to the reversal of the cycle »Zeus« begun twelve years before: »The cycle man, the little monkey, who the females tame here. It is the rotation of Zeus. Here the man was the aggressor.«

At the end Dieter Schrage sums up the work of Alfred Kornberger in the following words, »I survey over 20 years of paintings and graphic art by Alfred Kornberger, and I come to the conclusion: If the scenic painting, the tradition-bound, conjoined with Expressionism and in particular the French Fauvism needed an advocate in our time of many trends and fads, surely the would find such an advocate in Alfred Kornberger and his work.«

At the end Dieter Schrage sums up the work of Alfred Kornberger in the following words, »I survey over 20 years of paintings and graphic art by Alfred Kornberger, and I come to the conclusion: If the scenic painting, the tradition-bound, conjoined with Expressionism and in particular the French Fauvism needed an advocate in our time of many trends and fads, surely the would find such an advocate in Alfred Kornberger and his work.«

The article by Karl Benkovič in Kornberger's publication is concerned with a cycle of Kornberger, namely the cycle of »Neid und Hass (Envy and hatred)«, about the Apocalypse of St. John, which consists of ten oil paintings (see figure left).41

Benkovič points out that Kornberger had already sporadically dealt with the subject of the Apocalypse during the 1960s as well as related individual subjects like the way he had worked out the subject of the locust plague in 1989 in his paintings. The current cycle would not depict all of John's apocalyptic visions, rather only those which emphasize mostly the aspect of the dominance of evil and its attendant calamities and plagues. This cycle shows »a totally different Kornberger as that of the female paintings.«42

In the fall of 1989 presented a branch of the Zentralsparkasse Vienna, Währing, the exhibition »Alfred Kornberger und seine Schüler (Alfred Kornberger and his students)«. On display were works by participants of the private courses in the studio Kornberger.

In the following years Kornberger's exhibition activities decreased significantly. There followed only minor presentations in the private sphere, such as doctors' offices or business branches. In 1993 Kornberger was represented in the exhibition »Das Wiener Künstlerhaus in Schrems. Malerei (The Viennese Künstlerhaus in Schrems. Painting)« in Schrems, at the Kunstforum Waldviertel in the IDEA Design Center.43

In 1995 Kornberger exhibited paintings and decorating objects in the Jewel Studio of Irene and Martin Bogyi in Vienna-Währing. In the course of his repeated involvement with sculpture, Kornberger also encountered the object acting as jewelry miniature sculpture. He designed brooches with tiny plastic depictions of female nudes in gold, which were framed with a thin gold wire. These objects were an expression for the ingenuity the artist and his joy with experimentation, which was also reflected in other original works. Thus Kornberger created painted and glazed clay sculptures of about one meter in height, corpulent female figures representing beach costumes. Furthermore, there are many porcelain plates painted by the artist that show also nude sculptures.

At the same time in 1995 there appeared an article in the journal Vernissage by Maria Jelenko-Benedict, entitled »Alfred Kornberger. Geschlechterkampf oder Kampf dem Geschlecht? (Alfred Kornberger. Sex battle or battle of the sexes?)«.44 The author critically examines the eroticism radiating from Kornberger's female nudes. »The one and the same nude portrait expresses all the classic clichés about women: the female as child bearer, protector, self-revealer; but also the superior, the lust-arousing, who turns the male into a monkey through mere voyeurism.« The author questions the outdated stereotypes of women as weak, helpless victim who is subjugated to the greed of man. The woman as the ›being‹, the man as the ›acting‹, he the ›fire‹, she the ›water‹, etc. It is also striking that in his female nude (whether in the couple-representations, striptease scenes, or alone, masturbating), Kornberger represents the female as faceless, as if he wants to deprive her of any rationality and subsume her existence merely to that of the flesh.«

At the same time in 1995 there appeared an article in the journal Vernissage by Maria Jelenko-Benedict, entitled »Alfred Kornberger. Geschlechterkampf oder Kampf dem Geschlecht? (Alfred Kornberger. Sex battle or battle of the sexes?)«.44 The author critically examines the eroticism radiating from Kornberger's female nudes. »The one and the same nude portrait expresses all the classic clichés about women: the female as child bearer, protector, self-revealer; but also the superior, the lust-arousing, who turns the male into a monkey through mere voyeurism.« The author questions the outdated stereotypes of women as weak, helpless victim who is subjugated to the greed of man. The woman as the ›being‹, the man as the ›acting‹, he the ›fire‹, she the ›water‹, etc. It is also striking that in his female nude (whether in the couple-representations, striptease scenes, or alone, masturbating), Kornberger represents the female as faceless, as if he wants to deprive her of any rationality and subsume her existence merely to that of the flesh.«

Although Kornberger also treated socially critical aspects and issues of human hatred and terror, Jelenko-Benedict continues, the painter is dedicated to the good and the beautiful. In the middle point stands the glorification of femininity (see figure right). In his work, the artist transfers onto paper, »his respect, but also his desire as a man and lets his emotions lose. The erotic tension is also of course palpable, which the viewer imposes in a peculiar manner and which he can not evade.« Kornberger himself has expressed this feeling as follows: »Of course it is possible to paint without the nude. But to me it's about the exploration of the female body at the moment of painting, the erotic moment, which is transferred on to the drawing page, the depicting of an erotic landscape.«45

Despite the preference for the traditional oil painting, Alfred Kornberger also showed himself open to new media in his later years. Therefore, the skilled lithographer became especially interested in what new possibilities were opened up by the computer age for a graphic artist and painter. Despite his mature years he was not afraid to learn and work with the complicated graphic programs of the first computer generation. The result was a series of over fifty colored computer graphics that Kornberger in autumn of 1996. In these prints, the artist modified the already familiar motifs, where the curved line of the computer graphic programs replaced by the broad brush strokes of the painter. On the other, Kornberger created entirely new motifs, which are completely non-representational and depict curvy-linear shape formations.

On the occasion of his 65th birthday, there appeared an article in the journal Vernissage in 1998 on Alfred Kornberger, written by Eduard Arnold.46 The author illustrates in brief biographical descriptions the artistic beginnings of Kornberger. From the highly detailed explanations models it becomes clear that many of the statements in this article could have originated only from Kornberger himself, which he communicated to the author. In this respect, this brief text proves is proving to be a valuable source for some details from the biography of the artist, about the student period of with Professor Andersen or about his difficult beginnings as an artist.

During the last ten years of his life, Alfred Kornberger suffered from a serious illness. Trigger for this was among other things, his unhealthy lifestyle, his eagerness to work which led to his bodily exhaustion, and many sleepless nights, which were numbed by alcohol and nicotine. He repeatedly got dizzy spells and had to be hospitalized. Vienna's Wilhelminenspital became his regular shelter. There he fell into a coma-like state after painful attaches and from which usually awoke only days after. These agonies were always accompanied by gloomy premonitions and visions of death. As early as 1997 Kornberger noted on a sheet; »Death is the crowning of life. It is not appropriate to laugh about death or be afraid of it. Death is the most essential part of creation, because only with it can new life develop prepare for marriage with it.«

His wife Nevenka was by his side all through these difficult times. Since Kornberger mostly spent the night in his studio, it was specially a challenge for her to organize help for her husband in the case of a renewed collapse. As strong as was the pain that accompanied the recurrent seizures the artist never complained about it. Alfred Kornberger did let up. As soon as he had recovered somewhat, he plunged anew into the work and forgot all about the frailty of his body. In 1999, he underwent a successful eye operation.

In the later years he had more and more fainting spells. In-between, the healthy periods became shorter. His wife nursed him and tried to make life as bearable as possible for him. He did not experience the last attack in full consciousness. And yet his fully outstretched arm made a large circular motion. »He painted his last picture«, recalls his wife. On 31, March 2002, Alfred Kornberger died at the age of 69 in Vienna. On a small, undated piece of paper Kornberger had drawn with black felt pen to a death skeleton and next to it scribbled, »I await you. You are more honest than the living.«

Kornberger's work spans from the mid-1950s to the late 1990s. This period of the Modernism after 1945, was shaped in its international context by the dominance of informal and abstract painting, by Pop Art and Conceptual art up to conceptually oriented work with New media art such as Photography and Video art. Although Kornberger experimented with some of these directions, such as is the case with his kinetic material pictures, his work was largely focused on the confrontation with the representational depiction on the traditional altarpiece.

Especially in the years after 1945, the adherence to figurative painting was not self-evident. The main directions in Austria were shaped by the great currents of Informalism and Surrealism. The latter found its specific expression in Vienna through Fantastic Realism. In addition, Abstraction and Surrealism were afflicted with political connotations, they »bore witness to the identification with the politically welcome« Western art. Realistic painting, in contrast, was tainted with the odium of Socialist Realism, which was unsuccessfully propagated by the occupying Soviet forces. Hence, it was difficult for artists such Georg Eisler and Alfred Hrdlicka, to find recognition in the official art galleries in the 1950s.47 »The Austrian beginnings of a realist and critical art were easily demonized as ›Socialist realism‹ and artists who did not join with the abstract, were sidelined.«48

The discussion became more acute, as a not negligible opposition formed against abstraction by the traditionalists. The latter insisted on continuity with the art of 1945. To these belonged representatives of the generation that had created an important life work before 1945 is an important life's work, such as Graz based Rudolf Szyszkowitz, who fought a battle against the younger artists around steririscher herbst.49 There were just as well the representatives of the younger generation, who completed their studies only after 1945, but who explicitly joined younger generations, such as the, Styrian-born, Vienna resident Karl Stark, who was known expressly supported the continuation of the Austrian Expressionist painting.50 The artist who worked with figurative art stood diametrically opposed to the those working with abstraction, both sides fought a veritable culture war. Symptomatic in this context are the »Kulturbriefe (culture letters)« that Karl Stark regularly sent to the public in which he defended the ethical value of traditional painting.51

Ideas of the international modernism played an important role in these early years (see figure right). Undoubtedly a large momentum was triggered by the first exhibitions of the west European avantgarde that were brought back to Vienna for the first time after the war years. Here the activities of the French cultural institutes were groundbreaking, who if not out of political motives then for the victorious power of the French culture in the then occupied country. In the Viennese Museum of Applied Arts, the French Ministry of Culture organized the exhibition »Classiques de la Peinture Francaise modernes« in 1945. In this exhibition the development of the French painting from Impressionists through Paul Cézanne up to Cubism and subsequently to late Picasso and Léger could be viewed. But Surrealism was also represented with the early works of de Chirico and Max Ernst or Salvador Dali.

Ideas of the international modernism played an important role in these early years (see figure right). Undoubtedly a large momentum was triggered by the first exhibitions of the west European avantgarde that were brought back to Vienna for the first time after the war years. Here the activities of the French cultural institutes were groundbreaking, who if not out of political motives then for the victorious power of the French culture in the then occupied country. In the Viennese Museum of Applied Arts, the French Ministry of Culture organized the exhibition »Classiques de la Peinture Francaise modernes« in 1945. In this exhibition the development of the French painting from Impressionists through Paul Cézanne up to Cubism and subsequently to late Picasso and Léger could be viewed. But Surrealism was also represented with the early works of de Chirico and Max Ernst or Salvador Dali.

The search for a personal style, orientation towards the divergent, and the then highly current simulations by the International Modernism were symptomatic of the young generation after 1945. Kornberger's style pluralism, denounced by his newspaper critics as eclecticism, was an expression of such an orientation towards the French modernism. If this erratic search for the contemporary styles was characteristic of Kornberger especially for his early work, with other artistic personalities it spanned their whole life's work. Thus Romana Schuler in the work of Karl Anton Fleck speaks of an »immense stylistic pluralism«, which reveals an »apparent disorientation and instability«.52 Fleck first turned to Informal and Tachism in the early years, before turning to abstraction with geometric shapes. Starting in 1960 there emerged a turn to figurative representation.

Few people from Kornberger's generation had the opportunity to learn about contemporary French art in Paris. One of these Paris-fellows was Claus Pack (1921-1997) was. Pack had studied at the Viennese Academy under Herbert Boeckl had moved to Vorarlberg in 1946, where he lived as painter and literature- and art critic. In 1949 he was able to hold an exhibition at the Salon de Mai in Paris. By participating in the Internationale Hochschulwochen (International High School Weeks) in St. Christoph at Arlberg he came into contact with Maurice Besset, head of the French Cultural Institute in Innsbruck and initiator of the Hochschulwochen. In 1950 Besset helped Pack with a six-month scholarship for painting in Paris in 1950.

Claus Pack was deeply influenced by the formal language of Pablo Picasso and specially adopted the Cubist style of the great master. Even after his return from Paris the examination of Cubism remained the dominant theme of his painting style. Like Kornberger, Claus Pack was intrigued by Picasso up to his later works. According to Pack the art of Picasso creates a synthesis of space-time representations. »The object, still life or the figure appears beyond time and permanence.«53 Characterized in the eyes of Claus Pack is also Picasso's ability to shape in various forms. A metamorphosis of symbolic forms is developed. »A bicycle seat and bicycle handlebar turn into a bull's head, and the bull's head turns into a guitar.«54 Kornberger uses these same motifs when in his cycle »Zeus harassed a woman« he lets Zeus approach a woman in the form of a bicycle and mutates the bicycle seat into an erotic object.

Claus Pack had this in common with Alfred Korngerger that for both of them the Eros became the main theme of their late work. Even in this respect Pack and Kornberger found their legitimacy in the work of Pablo Picasso. Picasso's late work was entirely occupied by the male fascination for female eroticism. According to Werner Spies no other artist wanted to demolish taboos in such an exhibitionistic manner as Picasso did. Only, according to Werner Spies, Egon Schiele's Obsessions push aside the Spaniard's work in this respect.55

In addition, for Pack and Kornberger Picasso's late work was a justification of representational painting. The aesthetic discussion of the 1960s, which dealt almost exclusively with analytical theories and conceptual art rejected, a sensual, figurative painting, as Picasso practiced his later works. A painting that still clung to the traditional means of spontaneous pictorial gesture and a sensuous color in the objective illusion did not reflect the mainstream of the time. It was the more difficult for the painter Alfred Kornberger to hold onto representational painting pallet and produce a markedly sensual expression.

Especially in the drawing style, Alfred Kornberger oriented himself often towards Picasso's sweeping, not ending-endless line or shorthanded, almost emblemic drawing style of the late Henri Matisse. Just as the two French masters Kornberger also tends to widen the biomorphic body. »The curvilinearity of the outline is continued in the echo chamber of the drawing.«56 The harmonious calmness of female representation, their linier aesthetic and downright decorative gracefulness in the hands of Picasso and Matisse's are also continued in the work of Alfred Kornberger. They point to the classicistic character, which despite in all the innovations of the French avant-garde always continues to remain virulent.

Only toward the end of the 1960s, were the borders between figurative and abstract narrowed. Through Pop Art and the new media objectivity became once more a subject for the avant-garde, though in a new, altered form. Here, the painting was pushed more and more into the background. Concept art was the dominant trend. Even Kornberger's material images, such as »composition with dolls«, which he created in 1966, can be regarded as an original contribution to the Fluxus movement, and reminds one of the work of Daniel Spoerri or the Austrian André Verlon. In its conception as a »do-it-yourself-sculpture«, his »Quadri mobile« which also originated in 1966 recall, remind one of the Styrofoam cube, which Roland Goeschl had made available to the visitors of his exhibitions in much larger dimensions for their own use. 57

Finally, in his work »Composition with pre-established harmony« in 1968, Kornberger created a material image in which pieces of wood and other materials were bound to each other in a mobile form and could be set in motion by motor drive. The work ranks among the kinetic works that were produced in Austria by Curt Stenvert for example. Furthermore, in his cycle with painted machine images, on which he worked between 1966 and 1968, Kornberger also dealt with the techno effects of machine parts and geometric abstract shapes.

Besides Alfred Kornberger, Karl Anton Fleck also worked with the subject of machines in those years. More than Kornberger, Fleck moved the dialectic between man and machine to the center of his work. Most revealing in this context is the theoretical underpinning which Romana Schuler studied in her essay on Karl Anton Fleck and which in some ways also applicable in the case of Kornberger.58 Groundbreaking for the new awareness of the fact that that modern life is largely determined by new information media was the publication, in 1964, of the book »The magic channels. Understanding Media« by the media philosopher Marshall McLuhan. In this book McLuhan developed a theory of social change through the new information media, where the theoretician put forward the theses that the media function as a sort of prosthesis, which serve man for the understanding of the new world. A central theme presented by McLuhan in this context, is the close relationship between man and machine.

Similarly, the 1965 published work »Kultur und Gesellschaft (Culture and society)« by Herbert Marcuse exercised great social resonance. In this work also, the relationship between man and machine played a central role, where the philosopher considered the technique from a very critical point of view. Marcuse rejects an emerging, automated, technical future of the world. The provocative thesis of the Canadian communications scientist Marshall McLuhan were subsequently also received intensive reception by the German media theorists and cultural scientists, above all, as in the 1969 the German edition of »The magic channels« was published. Not surprisingly was above all the media artist Peter Weibel, who was the first in Austria to deal with McLuhan's offensively and critically reflected on it. Furthermore, Oswald Wiener, and Walter Pichler also dealt with this topic. Walter Pichler understood man as caught up in the constraints of architecture and machine. Man turns into part of an exercise apparatus, whose systems exert a threatening power.

Karl Anton Fleck, in turn, considered the human body as a machine that can be easily dismantled or reshaped. What results is mix hybrid of deformations of the human body. »The human body or the individual body parts like head, hands, feet are united as biological fragments with machines.«59 Indefinable, bizarre and grotesque creatures are transformed into ›anthropological machine‹.60 The anthropological character of machines or vice versa, the machine-like distortion of the human body plays a central role in the work of Alfred Kornberger. Unlike his colleague Karl Anton Fleck, Kornberger largely abstains from alienation effects that go beyond the formal integrity of the image. In the so-called »Zeus« cycle which Kornberger had worked on since 1977, the bike is transformed into a machine-like being. The technoid impression which is obtained by multiplying the wheel and the rod increases the anthropomorphic character of the car and at the same time turns into a threatening apparatus confronting the soft plumpness of the female nudes.

The close relationship between man and machine was not the only subject that the artist dealt with intensively in those years. In the late 1960s two exhibitions in short intervals took place in Vienna, each of which almost exclusively favored representational forms of expression. This surprising and unique positioning seemed symptomatic of a change in thinking, initiated in these years.

Firstly, it concerned the exhibition »Wirklichkeiten (Realities)« that took place in 1969 in the Vienna Secession and to which the six young artists were invited by the critic and journalist Otto Breicha. The works indeed display artistic positions, but were overall in the vicinity of a ironic-critical stance towards the contemporary Pop Art. Two of the protagonists of this exhibition, Peter Pogratz and Franz Ringel, showed closeness to nature, to the Art Brut and the COBRA group. Works from this environment, distort the representation of humans into the grotesque, the female nudes appear as rough, large-breasted female forms with distorted faces. The Dutchman Willem de Kooning, one of the representatives of the COBRA group, shows depictions of crowded images of women that he created with a frenzied brush strokes on the canvas.61 Kornberger also moves to the vicinity of these artists in many of his picturesque, finely crafted nudes and is familiar with such dramatic and ecstatic scenes that correspond to a creative will which is oriented towards immediacy.

In 1969 the Zentralsparkasse (Central Savings Bank) of the City of Vienna, under its then cultural advisor Dieter Schrage, organized an exhibition under the title of »Figur (Figure)«. The Stuttgart-based art critic Karl Diemer gathered the five Viennese artists Georg Eisler, Alfred Hrdlicka, Fritz Martinz, Rudolf Schoenwald and Rudolf Schwaiger, all of whom aligned themselves explicitly with the unusual realism of the time . In a broader sense Karl Stark would also count in this group.

Especially in the works of artist friends George Eisler and Alfred Hrdlicka the forms of realism concealed a socio-critical component. Eisler, who was forced to flee Vienna for England where he became acquainted with Oskar Kokoschka, painted mostly pictures on the subject »Menschen in der Großstadt (People in the city)«. The phenomenon of the anonymous human mass was repeatedly present in his multi-figured depictions and topographical views of the cities. Georg Eisler used a naturalistic style with the hastily acting, gestural brushwork to produce a special light mood and atmosphere.62 There is a great similarity between Eisler's atmospheric studio views and the studio scenes of Kornberger. Just as George Eisler, who prefers to leave his protagonists in anonymity, Kornberger also refused to describe his female figures further in detail, but often elucidated them only dimly.

The figures of Alfred Hrdlicka always unite great readiness for violence. Hrdlicka has created a proletarian world view in which man, in his decrepit creatureliness, is subjected to its own aesthetic, which is completely opposed to the conventional taste. Aging, overweight body types populate most of his drawings. But always they are protagonists of most cruel histories and genre paintings with social critical component.63 This violence with its raw, brutal form is featured subliminally many works of Kornberger. Yet Kornberger's at times equally coarse nude figures always move in the context of an aesthetic discourse of the studio scene and not, like Hrdlicka, as part of a theatrical narrative.

The subject of the human confronted with violence is also pursued by Austrian artist Adolf Frohner. Like Alfred Kornberger, only about one year younger Adolf Frohner concentrated especially on the representations of the female nude. Frohner comes from the school of Actionism, and is rightly considered one its cofounders. With the material images from the Actionist period Adolf Frohner, together with the material sculptures by Oswald Oberhuber, is one of the first to break out of the boundaries of the panel painting. Subsequently, he returned to the traditional, realistic painting and also moved into the vicinity of the group »Figur (Figure)«.64